The University of Stirling is fortunate to possess a collection of fourteen paintings by the twentieth-century Scottish painter John Duncan Fergusson.

These were presented by the artist's widow, Margaret Morris, when the University was founded in 1968, as a mark of her friendship with Tom Cottrell, its first Principal, and her excitement at the inauguration of a great new adventure in Scottish education. She had been with Fergusson for the best part of fifty years, sharing a full life of artistic adventure.

The first of four children, J. D. Fergusson was born on the ninth of March, 1874 at 7 Crown Street in Leith, Edinburgh. After the Royal High School, the idea of being a naval surgeon appealed briefly to an increasingly adventurous spirit, but Fergusson perhaps did not take his studies too seriously and soon realised that his vocation was to paint.

In 1898 he was in Paris studying in the Louvre and was deeply impressed by the Impressionist paintings in the Salle Caillebotte. During these years the strongest influence on Fergusson was his friend S. J. Peploe. Peploe was three years older and by the time they met in about 1895 had already studied in Paris and had been to Amsterdam, bringing back reproductions of paintings by Rembrandt and Hals. Like Peploe, Fergusson's concern was for the nicety of tonal relationships, elegance of design and an alla prima virtuoso technique in oils.

Fergusson made a trip by tramp steamer to Southern Spain and then Morocco, probably in 1897, and as he acknowledges in his own book, Modern Scottish Painters, his oils and watercolours show the influence of Arthur Melville, who had made similar painting excursions ten years earlier. The watercolours are executed in a blottist technique while the oils, like Bazaar in Tangier, are loosely painted and, although limited in palette, look forward to his landscapes of the next ten years in which strong colour becomes increasingly important.

In the early years of his painting career Fergusson worked obsessively to perfect his style. He began exhibiting regularly with the Royal Society of British Artists, where he became a member in 1903, and later at exhibitions in London at the Baillie and Stafford galleries, as well as at the Society of Scottish Artists and the Royal Glasgow Institute in Scotland.

The rejection of a tight academic finish and the development of powerful, evident brushwork had become characteristic. At this stage his subject matter was confined to portrait, still-life and landscape on a small scale, but for Fergusson form would always outweigh content: his pictures are neither symbolic nor meretriciously anecdotal, but his colour and the rhythms and forms he paints are highly suggestive. As Andre Dunoyer de Segonzac wrote in his foreword to Fergusson's memorial exhibition of 1961: 'His art is a deep and pure expression of his immense love of life. Endowed with a rare plastic feeling, almost sculptural in its quality. he joined with it an exceptional sense of colour, outspoken, ringing colours, rich and splendid in their very substance'.

The regulars in Bar at Public House circa 1900 are no doubt drinking Scottish ale, but within a short time his cast would become French. From the turn of the century, Fergusson began to spend more time in France on extended painting holidays in the North, often with Peploe, in Etaples, Paris- Plage, Deauville, Le Touquet, Dieppe and of course Paris. The Seine at Charenton, an industrial townscape, was perhaps painted as an antidote to the elegance of the Edwardian resort towns he was chiefly painting, but stylistically it is the same as his beach scenes and promenades.

Fergusson acknowledged a debt to Whistler, whose influence is evident in The Feather Boa of 1904. Like many others, this picture seems to celebrate the artist's admiration of strong stylish women. He moved to Paris in 1907 and this was the painting he chose to exhibit in the Salon d'Automne, surprising perhaps, two years after Fergusson had watched the Fauves burst upon the scene at the same venue, and while his own work was undergoing a dramatic change.

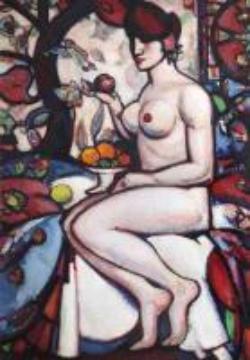

In Self Portrait of 1907, Fergusson depicts himself in brutal terms, as if he would revel with Matisse and Derain in the epithet Wild Beast. In this picture and The Red Shawl, a portrait of the American writer and critic Elizabeth Dryden, the human subject stands before a strongly patterned, abstract backdrop and there is little sense of real space. At about this time, Fergusson asks his women to take their clothes off- and never lets them get dressed again. A transition work is the sumptuous Voiles indiennes where the pattern making, the respectfully painted, linear perspective and the softness of the female figure (whose draped lower half seems to fulfil Fritz Kriesler's assertion that women are solid from the waist down) make for a rather awkward picture.

There is nothing tentative about Rhythm of the next year, which is perhaps Fergusson's first modernist masterpiece. The young John Middleton Murry visited Fergusson in his studio in 1910 and when preparing to launch a literary periodical some months later, borrowed Rhythm as the title, and a graphic representation of the painting for his cover, as well as asking Fergusson to become art editor. In this capacity Fergusson commissioned work for illustration from Derain, Marquet, Segonzac, Friesz, Picasso, Larionov, Gontcharova, Gaudier-Brzeska, Peploe and Anne Estell Rice, an American painter who was by now his lover. And of course himself. Most of these, along with Chabaud and Delaunay, he had met through the Salon d'Automne. Also in Paris at the time, and fellow habitués of the Bohemiancafes were Jessie M. King and E. A. Taylor, and Jo Davidson, an American sculptor whose portrait Fergusson made in bronze. He wrote of these extraordinary times with enormous affection and his paintings and many drawings of such places as the Pre- Catalan Restaurant, the Cafe Harcourt and the Closerie des Lilas describe a night-life of music, gaiety and absinthe-fuelled abandon.

His subjects were still on the whole those of convention: still-life, landscape and the nude, as well as quick portraits of friends, a charming example of which is Pam 1910. There is no reason to suppose that Fergusson disliked women's hair, but every reason to suppose that he loved them in hats. Rhythm and particularly Les Eus of 1911-12 owe something to the celebrated dance movements of Isadora Duncan's theatre, but more importantly Fergusson is subordinating his motif to the whole design; the personality of the figure is lost, and the spatial reality of still-life objects becomes secondary to a rhythmic orchestration, realised in uniform brushstrokes.

Fergusson wrote in his Memories of Peploe 1945 of the wonderful seasons of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes: Sheherazade, Petruchka and Sacre Du Printemps.Fergusson was by now a societaire of the Salon d'Automne as was Leon Bakst, whose designs for the Ballets Russes, along with the physicality of the dances, proclaimed a vitality paralleled in Fergusson's paintings. In the summers Fergusson would go on holiday. In 1910 it was to Royan where Peploe's son Willie was born, the next year to Brittany, to the Ile de Brehat and in 1913 to Cassis near Marseilles. With his studio in Paris being prepared, Fergusson stayed in the South, taking a house at Cap d'Antibes. His return to London for an exhibition of forty-seven works at the Dore Galleries in 1914, coincided with the outbreak of the First World War.

Fergusson first met Margaret Morris in London in 1913. Morris lived with her mother, running her dance school around which an astonishing circle of friends gravitated: Bernard Shaw, Edith Sitwell, Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis. Fergusson divided his time between London, where he could be with Margaret Morris, and Edinburgh, where he stayed with the Peploes .

Fergusson had taken part in several prestigious group exhibitions in the preceding years and was considered to be in the vanguard of British modernist painting. The frustration of a war-bound Europe, and the hardship that the lack of sales brought, meant that during this period he achieved little; until 1918. Though he was not an official War Artist, he was encouraged by a friend in the War Ministry to travel to Portsmouth and paint in the naval dockyards. Although the Nation ultimately missed the opportunity of acquiring any of the resulting pictures, the machinery of war and modern majesty of the ships, submarines and naval architecture had a catalytic effect on Fergusson's painting.

Portsmouth Docks 1918, with its towering verticals, dramatic viewpoint and the monolithic intrusion of a destroyer's bow, is not concerned with war but with power and energy. This, along with the planar method of construction, allies the picture to Futurist and Vorticist preoccupations.

By this stage he was settled into a studio at 15 Callow Street, SW3, where he was to remain until 1929. Deeply involved with Margaret Morris, he attended all her summer schools, at Ilfracombe (1917-1918), Harlech (1919- 1921) and Dinard (1920). In 1923 he made a painting tour of the Scottish Highlands. It was during this trip that he painted In Glen Isla, a picture which shows a debt to Paul Cezanne and in its architectural approach to landscape heralds a new maturity in Fergusson's art. Many of the paintings from this trip were shown in his first major exhibitions in Scotland, at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh, and then at Alexander Reid's Gallery in Glasgow. New horizons were opening and in 1926 he had his first exhibition in New York, at the Whitney Studio, and in the preceding year showed with Peploe, Hunter and Cadell at the Leicester Galleries in London. In 1928 he had four major exhibitions: in Chicago, London, Glasgow and New York.

It was in the next year he returned to France, once again taking a studio in Paris, in the rue Gazan, near the Parc de Montsouris, and spending his summers at Cap d'Antibes.

In 1931 he was involved in an exhibition of six Scottish artists in Paris at the Galerie Georges Petit, when the French Government bought one painting for the Luxembourg. He also found time to return to Dinard. Dinard: The Quay recalls the Portsmouth painting in its viewpoint but the machinery of war has been replaced by the appurtenances of leisure.

In contrast to the romantic stereotype, Fergusson did not suffer for his art. His spirit was too ebullient and generous for such self- indulgence. But his pictures are never glib or slick and in each picture the rewards of a painterly struggle are evident. He had a sense of his own greatness and was prepared to tackle ambitious subjects on a grand scale. Bathers: Noon 1937 has overtones of Cezanne's Bathers series but seems of its own period in respect of its art deco stylishness.

Once again the shadow of war loomed over Europe. Fergusson and Margaret Morris left Paris and moved to Glasgow. They took a studio flat at 4 Clouston Street, where Fergusson spent the last years of his life. The Scottish art world rumbled on and Fergusson was now a slightly beleaguered figure, never to, be absorbed into the academic fold or embraced by the Royal Scottish Academy. But many much younger artists gravitated towards Fergusson and in 1940 he founded the New Art Club, out of which emerged the New Scottish Group of painters of which he was the first president. Glasgow at least had taken him to its heart and he had his first retrospective exhibition in the city in 1948 and received an honorary LLD at the University in 1950. He continued to make annual trips to the South of France during the 1950s, but perhaps, his powers waning, painted mainly watercolours. He did paint Glasgow subjects - particularly on the river Kelvin near his home. A Bridge on the Kelvin, with its refracted light and rich, sonorous colour, recalls the late Monet, painting at Giverny, and seems exemplary of a new, soft lyricism. He died in Glasgow on the 30th of January 1961.

GUY PEPLOE