Inspired by his father, who played alongside Pelé, Donald Veronico Alves da Silva is aiming to tackle racism in Brazilian football through his research, with the support of a visiting scholarship to the University of Stirling.

Researcher

I had a black coach in my house all of my life, and in some moments, I didn’t understand some of the things that happened to him professionally. Now, through my research and as I study more, the racism black sport coaches suffer is very clear to me.

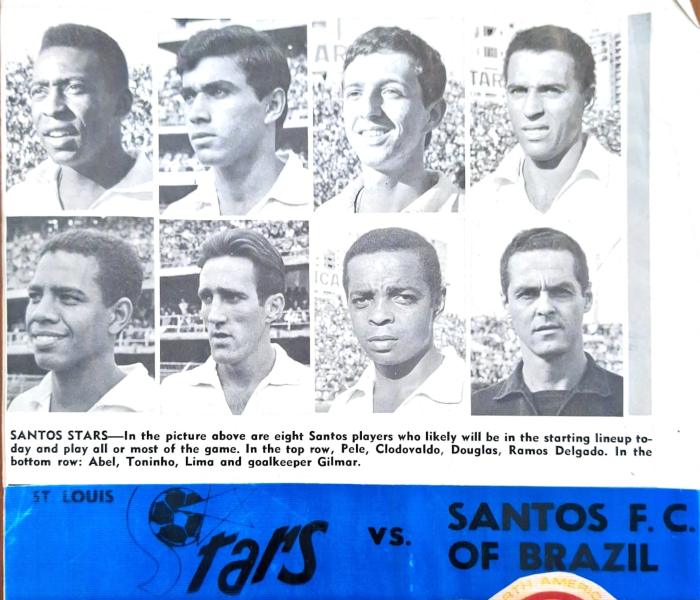

Donald Silva was born in Mexico, while his father – football star, Abel Veronico – continued his professional playing career. Abel had started his career in Rio, before joining the world-famous Santos Futebol Clube where he played alongside football legend Pelé. Donald and his twin brother Douglas went on to spend some of their childhood in Qatar, where his father coached.

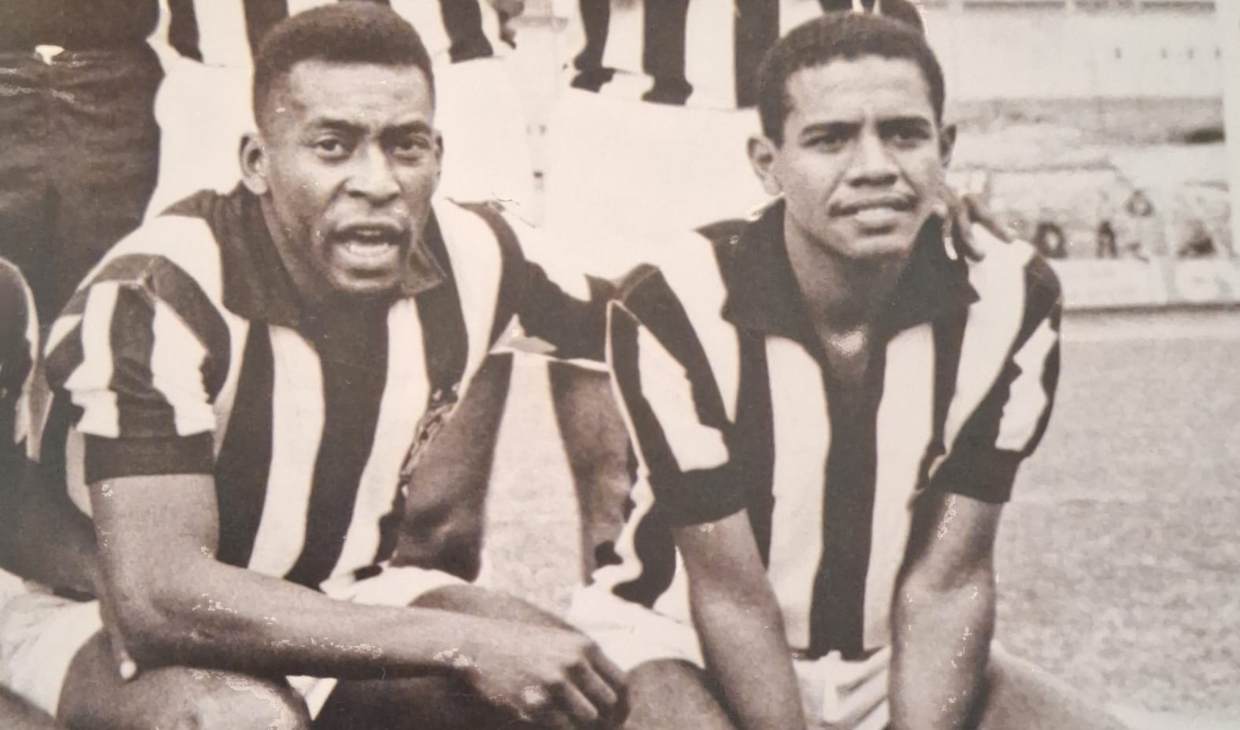

Abel Veronico (right) played alongside Pelé at Santos Futebol Clube

Abel Veronico (right) played alongside Pelé at Santos Futebol Clube

“Although I was born in Mexico, I am very much Brazilian,” says Donald. “Our names were picked from a baby naming book and I’m certain my mother had no idea they were Scottish. I’ve yet to meet another Donald in Brazil!

“I am from Santos, and I have a bond with the team, not only as a fan but through my father, who is known as an ‘eternal idol’, like an ambassador of the team.

“I tried to follow my father’s career, but I didn’t have the talent, so I moved on to my studies and became a sport manager and have been working in sport and development programmes in Santos for almost 15 years.”

Donald originally explored discrimination in Brazilian sport as part of his Physical Education undergraduate degree. A Masters in Financial Law in Sport followed, before he decided to pursue a PhD at the University of São Paulo, supervised by Dr Flavia Bastos.

Donald says: “I started to think about what is motivating me to study – a PhD is long, it is a lot of dedication and study. I came back to my life history as a black man, of a person who has suffered racism and discrimination in my country, who saw my father experience racism and discrimination in football, and as someone who has worked and volunteered for this cause.

“I am specifically studying the link between racism and the under representation of black coaches in the elite football league in Brazil. Here in the UK, and also in the USA, there are many researchers who have been studying the representation of minority groups in sport coaching – in Brazil, there is very little material and data on this topic.”

During his six months as a visiting scholar at Stirling, which has been financed in part by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – a public governmental Brazilian agency which supports postgraduates in the country – Donald will work under the supervision of Dr Claudio Rocha.

Stark results

As part of his research, Donald has analysed more than 1,000 players and 65 coaching staff in Brazil’s top football league, finding stark results.

Donald says: “Brazil’s legislation is fairly progressive as far as combating racism and racial inequalities in society – we have many laws and some affirmative actions; quotas in our educational system and public jobs, for example. But social and racial inequalities in Brazil remain huge – black people are found to earn the lowest salaries, have the least educational and employment opportunities, and live in the poorest areas.

“My initial research has found that racial inequality in elite football in Brazil is even worse than in its society as a whole, and likely one of the worst, if not, the worst in the world,” he explains.

“Through my analysis, I identified that despite black Brazilian players accounting for around 57% of footballers playing in Série A – Brazil’s top league – they accounted for only 17% of coaching staff, whether head coaches or assistant coaches, and zero, simply none, were represented in the top leadership positions.”

Racial inequality in football is not a new scenario in the country, according to Silva.

“Football was brought to Brazil by an Englishman in the late 19th century, at around the same time as the abolition of slavery in the country. Black people weren’t allowed to play football – it was an elite sport played in schools and clubs that they didn’t have access too. As time has moved on it became a diverse sport as far as playing is concerned – with a pair of shoes and an orange, for example, black kids could play in the street.

“In 1950, Brazil hosted the World Cup and we lost to Uruguay, and it was our goalkeeper – a black man – who became the scapegoat for the loss. In 1958, the first time Brazil took the title in the World Cup, we saw black players discriminated against with Pelé and Garrincha started on the bench. However, the players broke down barriers on the pitch and the national team’s success helped project a belief that there was racial democracy and equal opportunities for all in Brazil – which wasn’t the case.

“I had a black coach in my house all of my life, and in some moments, I didn’t understand some of the things that happened to him professionally. Now, through my research and as I study more, the racism black sport coaches suffer is very clear to me.

A recent photograph of Donald with his father, Abel Veronico

“During the period we lived in Qatar, my father was nominated best head coach of the year, amongst many top-level coaches from Brazil and the world that were working there at that time. When we came back to Brazil a year later my father did not get any job opportunity in any Brazilian team, whereas the same coaches that were in Qatar, did. They were white.

“Still now, we are in this horrible situation where we have this huge problem at the very top of the game. That’s why I’m here in Stirling – to learn, study, exchange, and to go back to my country to continue my research; take back what I’ve learned and try to contribute to an equal and diverse society in and through sport."